Quick Dive: Meta Platforms

Meta’s Moat: Scale, Strategy, and the Founder Behind It

Dear readers,

In this quick dive, we’ll attempt to break down the business of Meta Platforms (NASDAQ: META) and understand what makes this company special. Apologies as this post is slightly longer than expected, but we hope you enjoy it!

Financial Snapshot

About Meta Platforms

Meta Platforms operates as a social technology company. They build products that help people connect and share with friends and family through mobile devices, personal computers, virtual reality headsets, and wearables worldwide. Meta operates in two segments: Family of Apps (“FOA”) and Reality Labs.

The FOA segment comprises Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, WhatsApp and Threads. The Reality Labs segment provides augmented and virtual reality related products comprising consumer hardware, software and content.

Meta generates substantially all of their revenue from selling advertising placements on their FOA to marketers. Ads on their platform enable marketers to reach people across a range of marketing objectives, such as generating leads or driving awareness. Reality Labs generates revenue from sales of consumer hardware products, software and content.

Meta’s ad revenue is broadly a function of ad impressions and ad price. When Meta introduces a new product or feature, such as Stories or Reels, the feature enters a growth stage, where ad impressions surge due to increasing user engagement, while ad prices decline. This initial drop in ad prices occurs because advertisers may be hesitant to allocate significant budgets until they understand the new format’s effectiveness, leading to lower initial advertiser demand and weaker competition for ad slots. At the same time, high user engagement generates a rapid increase in ad inventory, and if Meta hasn’t fully optimized its ad load, this oversupply of ad inventory further depresses ad prices.

As adoption grows, the feature typically drives a substantial share of user activity on Meta’s platforms, making them a primary engagement surface. Over time, as engagement plateaus and adoption stabilizes, the feature transitions into the mature stage, where impression growth slows, but ad prices rise. Advertisers gain confidence, optimize their campaigns, and competition for ad slots intensifies, driving up ad prices and improving monetization efficiency.

Throughout Meta’s history, the company has followed a recurring cycle: launching new features to drive user engagement, then integrating ads, and optimizing the ads for monetization; this pattern drives shifts in ad impressions and ad prices over time, as shown in the diagram below:

The effectiveness of Meta’s ad ecosystem is ultimately driven by its scale. With 3.35 billion daily active users, its network effect amplifies both engagement and monetization.

To put that into perspective, Statista estimates the global internet population at approximately 5.52 billion as of October 2024. However, China’s 1.1 billion internet users (as of June 2024) are largely excluded from the global digital ecosystem due to the “The Great Firewall”, which acts as a digital barrier by restricting access to foreign platforms and censoring the internet for its citizens. Adjusting for this, the effective global internet population is about 4.42 billion. With 3.35 billion users, Meta has about 76% of the effective global internet population across its apps.

Even at this enormous scale, Meta’s network still continues to grow, though at a slower pace than before. Here's Meta’s daily active users for the past nine quarters:

In line with Metcalfe’s Law, with each additional user, the value of Meta’s network increases exponentially, not linearly. The size of this network is not only unparalleled — it’s also often underrated. Even if user growth slows, as long as the user base remains stable and doesn’t decline significantly, there will still be opportunities for revenue expansion.

With billions of users deeply embedded in its ecosystem, Meta benefits from self-reinforcing network effects that strengthen its competitive position. But beyond scale, there’s another key advantage: a part of Meta’s business that appears to be antifragile.

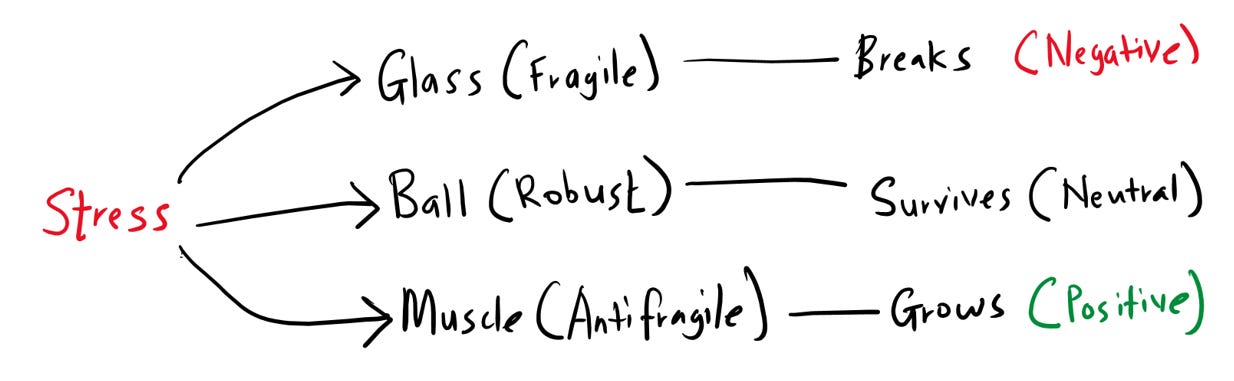

The term “antifragile”, coined by Nassim Taleb, is described as the logical opposite of fragile. Taleb emphasized that antifragile should be distinguished from robust. Something robust can withstand stress relatively well, but will eventually break. In contrast, something antifragile would not only be able to withstand stress, but also benefits from it. The example below illustrates how fragile, robust and antifragile systems react to stress:

Ben Thompson, author of the technology newsletter Stratechery, pointed out an element of antifragility in Meta’s business, allowing it to not only survive but also benefit from disruptive macroeconomic events such as COVID-19.

Given Meta’s ad model operates on an auction-based system, economic downturns tend to reduce ad spending by short-tail advertisers — big brands or a small group of high-spending advertisers — leading to lower ad prices. As brand advertising declines, long-tail advertisers — small to medium businesses or a large number of lower-spending advertisers — are incentivized to increase their ad spend because lower competition reduces costs, making ads more efficient and improving their return on investment.

Consequently, the decreased demand from short-tail advertisers would initially lower Meta’s profits. But as long tail advertisers capitalize on the lower ad prices, Meta’s profits could eventually see more upside than before given the larger proportion of long-tail advertisers on its platform.

Zuckerberg’s Integrity: The Controversies, Misconception and Realities

One of Meta’s biggest competitive advantages is its founder and CEO, Mark Zuckerberg. From being labeled a robot and the ‘Lizard Man’ to his MMA phase and supposed MAGA era, his reputation has been nothing short of controversial.

In investing, a CEO’s integrity is critical. When you invest in a company, you’re trusting management to be a responsible steward of capital. A leader’s values, decisions, and long-term vision can significantly impact shareholder returns.

Zuckerberg’s integrity, however, has been a subject of debate, largely shaped by media narratives and past controversies. Many common perceptions about him may be oversimplified or even misleading. Understanding his true character requires looking beyond the headlines; a deeper dive into these key moments reveals a more nuanced perspective on his integrity.

Winklevoss Twins and Saverin: Early Betrayals or Business Realities?

The first major controversy surrounding Zuckerberg dates back to Facebook’s founding, with the claim that Zuckerberg stole the idea from Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss and Divya Narenda. The Winklevoss twins alleged that Zuckerberg copied their concept for a social networking site and misused the code he was hired to develop for their project, ConnectU.

However, the reality is more nuanced. By the time Zuckerberg was approached to work on ConnectU in November 2003, several social networking platforms already existed — Friendster had launched in March 2003, followed by MySpace in August. Even Harvard itself wasn’t new to the concept; Aaron Greenspan, a junior at Harvard during Zuckerberg’s time, had built houseSYSTEM, a website that included a student directory and used the “Harvard.edu” domain for verification. Further, Stanford had implemented a similar system as early as 1999.

The Winklevoss twins argued that their key differentiator — the idea of a verified, exclusive student network — was stolen. But in truth, this concept was already being explored by others. What Zuckerberg did was synthesize existing ideas, refining them into something more compelling.

That said, young Zuck wasn’t entirely blameless. The infamous AIM chat logs reveal that he deliberately stalled the ConnectU project to ensure Facebook launched first:

“Someone is already trying to make a dating site. But they made a mistake haha. They asked me to make it for them. So I’m like delaying it so it won’t be ready until after the facebook thing comes out.”

“Yea, I’m going to fuck them, probably in the ear.”

While Zuckerberg’s actions show a mix of cutthroat competitiveness and immaturity, they don’t amount to outright dishonesty. His competitive nature led him to make questionable decisions — such as delaying the ConnectU project — but there’s no clear evidence that he outright stole the idea. Instead, he synthesized existing concepts and executed them better. Rather than a case of cheating, it was a young entrepreneur making aggressive, and at times, reckless moves to win — a reflection of his immaturity at the time rather than a lack of integrity.

Another common misconception is Zuckerberg’s alleged betrayal of Eduardo Saverin, Facebook’s co-founder and initial financier. Popularized by The Social Network, the narrative suggests that Zuckerberg ruthlessly betrayed his friend by diluting his shares and forcing him out of the company.

In reality though, the situation was more complex. Saverin had been responsible for securing funding and handling Facebook’s business side, but he struggled in his role. Meanwhile, he launched Joboozle, an online job board that could have competed with Facebook – then he advertised it on Facebook without approval and at no cost. Zuckerberg’s frustration was evident in his emails:

“You developed Joboozle knowing that at some point Facebook would probably want to do something with jobs. This was pretty surprising to us, because you basically made something on the side that will end up competing with Facebook and that's pretty bad by itself. But putting ads up on Facebook to advertise it, especially for free, is just mean.”

Zuckerberg saw Saverin as a liability, repeatedly expressing concerns about his lack of contribution:

“I maintain that he fucked himself…He was supposed to set up the company, get funding, and make a business model. He failed at all three…Now that I'm not going back to Harvard I don't need to worry about getting beaten by Brazilian thugs.”

"Eduardo is refusing to co-operate at all…We basically now need to sign over our intellectual property to a new company and just take the lawsuit…I'm just going to cut him out and then settle with him. And he'll get something I'm sure, but he deserves something…He has to sign stuff for investments and he's lagging and I can't take the lag."

Zuckerberg, who has admitted to being conflict avoidant — especially in his youth — likely mishandled the situation, allowing tensions to escalate. However, his decision wasn’t driven by malice; Saverin had become a weak link, and removing him was a difficult but necessary business move. While Zuckerberg’s approach lacked tact and emotional intelligence, it wasn’t an act of betrayal or dishonesty. Instead, it highlights his ability to make tough decisions when the company’s future is at stake — even when it means cutting ties with a friend.

The Cost of Openness: Facebook’s Recurring Dilemma

From its early days, Facebook was built on the idea of openness — Zuckerberg believed that sharing more, not less, would ultimately benefit users and society. This philosophy shaped many of the company’s decisions, but time and again, it led to crises that tested the limits of user trust. Three key controversies illustrate a recurring pattern: Facebook defaulting to openness without fully considering the consequences.

One of the earliest examples of this was the introduction of the Beacon program in 2007, where Facebook partnered with commercial websites to track user activity. Facebook’s early approach to privacy was rooted in an “opt-out” model, meaning users were automatically included unless they actively chose to withdraw. If a user purchased dog food or booked a flight online, this information could automatically appear in their Facebook News Feed, notifying friends – often without the user’s explicit awareness.

Although Facebook provided a pop-up warning with opt-out instructions, many users either missed or ignored it. Worse, if they didn’t take action, Facebook interpreted this as consent. While Zuckerberg likely saw Beacon as an extension of Facebook’s transparency ethos — encouraging sharing by default – he underestimated the potential backlash. The program exposed sensitive purchases, including medical supplies, adult products, or surprise gifts like engagement rings, which sparked public outrage.

The key issue wasn’t just the tracking itself but the failure to properly inform users. This pattern – defaulting to public settings without clear notice — would become a recurring criticism in Facebook’s handling of privacy.

Years later, a different kind of crisis emerged — not about privacy, but about the unintended consequences of an open platform. As Facebook’s user base exploded, so did the spread of misinformation. While fake news has always existed, Facebook’s News Feed algorithm amplified its reach, prioritizing high-engagement content —often sensationalist or misleading stories. This created a fertile ground for political disinformation and ad revenue-driven hoaxes, as users rarely fact-checked sources.

A common tactic was to create fake news outlets with names resembling real ones, such as “Denver Guardian”, which falsely appeared affiliated with The Denver Post. Political disinformation campaigns leveraged Facebook’s reach to manipulate voters’ emotions.

Zuckerberg’s initial stance was probably too idealistic — he believed in free speech and resisted in making Facebook the “arbiter of truth”. He assumed that users could discern fact from fiction, but reality proved otherwise. The consequences of this miscalculation were severe. In the U.S., misinformation campaigns played a role in shaping voter perceptions during the 2016 presidential election, while in Myanmar, unchecked hate speech on Facebook was linked to inciting violence against the Rohingya Muslim minority.

Following criticism, Facebook massively expanded its safety, security and content moderation teams to address misinformation proactively rather than reactively. Zuckerberg later admitted he underestimated the impact fake news could have on elections.

This miscalculation wasn’t about Zuckerberg protecting bad actors or personal gain, but about overestimating the benefits of openness. He saw Facebook as a neutral tool rather than an active gatekeeper of truth. However, this idealistic stance ignored the reality that misinformation spreads faster than facts, and bad actors could manipulate engagement-driven algorithms. The controversy forced Facebook to rethink its role in political discourse, revealing a flawed assumption: openness alone doesn’t lead to better outcomes. His mistake wasn’t dishonesty, but rather a failure to anticipate how the system could be abused.

If Beacon was an early warning and fake news a credibility crisis, Cambridge Analytica was a full-blown scandal. Cambridge Analytica wasn’t an isolated incident but rather the most infamous example of Facebook’s lax data-sharing policies.

In 2010, Facebook introduced Open Graph (Graph API v1), which allowed developers to access user data — not just from people who used the app, but also from their friends. This meant millions of users had their personal information unknowingly harvested without explicit consent.

Facebook claimed that third-party apps could only collect data necessary for their function, but in reality, developers could extract nearly all personal details from a user’s profile. Worse, there were no robust safeguards to ensure developers didn’t misuse or resell the data.

One developer, Aleksandr Kogan, created an app called This is Your Digital Life. His app collected data from users and their friends, which he later sold to Cambridge Analytica under the guise of academic research. The firm repurposed this data for political microtargeting during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections and Brexit referendum.

Cambridge Analytica wasn’t the only culprit. Facebook later discovered that over 400 developers had violated its data policies. In response, Facebook suspended 69,000 apps, including 10,000 suspected of misusing user data.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal exposed the risks of Zuckerberg’s overly idealistic approach to openness. Zuckerberg initially saw open data access as a way to empower developers and build a more interconnected platform, but without proper oversight, it became a liability. It also exposed how little control Facebook had over its own ecosystem.

Zuckerberg’s mistakes weren’t driven by a desire to exploit users but by an idealistic faith in openness and innovation. He believed that giving developers access would lead to better products and experiences, failing to recognize how easily this trust could be abused. His flaw wasn’t malice, but naïveté — assuming that others would act in good faith and that minimal oversight wouldn’t lead to major consequences. While he bears full responsibility for not implementing stronger safeguards, the narrative that he deliberately sought to profit at users’ expense oversimplifies the reality. His biggest failing was not deception, but a reluctance to acknowledge that openness without guardrails could be dangerous.

From Beacon to Fake News to Cambridge Analytica, the pattern seems clear: Zuckerberg’s mistakes weren’t rooted in deception or self-interest, but from an idealistic belief in openness, transparency, and innovation. He assumed that people wanted to share more, that free speech would self-regulate, and that developers would act responsibly. Each time, reality proved more complex than his vision allowed.

His integrity isn’t in question, but his judgment has been. He was slow to recognize the darker side of Facebook’s scale and influence, repeatedly assuming that Facebook’s openness and transparency was good for society. The real lesson isn’t about dishonesty — it’s about the unintended consequences of moving fast without fully understanding what you’re breaking.

Zuckerberg Nation and his Paternalistic Vision

Much of Zuckerberg’s idealism is rooted in a form of paternalism — the belief that he knows what’s best for users, even if they don’t realize it themselves. This mindset is similar to that of a king who believes he knows what’s best for his subjects, rather than leaving them entirely up to public consensus. He has often pushed forward with changes that he believed would improve Meta in the long run, even in the face of intense backlash.

One such example is News Feed. When Facebook introduced it in 2006, users were outraged, believing that it was intrusive and a violation of privacy. The backlash was so intense that users staged protests, and the Palo Alto Police Department even called Facebook, asking them to shut down News Feed to calm the chaos. Despite the uproar, Zuckerberg held firm, believing that News Feed would drive engagement and improve the platform. He was right — engagement on the platform surged, and as users adapted, News Feed became one of Facebook’s defining features.

While Zuckerberg sees openness and transparency as inherently positive forces, he has frequently underestimated how uncomfortable users are with losing control over their personal information. The challenge he faces is best captured by James Grimmelman, a professor of law and technology at Cornell University, who notes:

“There’s a deep, probably irreconcilable tension between the desire for reliable control over one’s information and the desire for unplanned social interaction.”

With billions of users, Meta operates at a scale where decisions are bound to be polarizing — what some see as innovation, others perceive as intrusion. This amplifies both successes and failures, making Zuckerberg’s mistakes more scrutinized and, at times, sensationalized.

What complicates thing further is that the perceptions of Meta’s actions aren’t universal; cultural differences shape how people react. In the West, where individual privacy and digital rights are paramount, changes to data policies or content moderation often spark backlash. In contrast, many Asian markets tend to be more pragmatic, prioritizing convenience and functionality over privacy concerns. This divergence creates challenges for Meta’s global strategy, as a single policy can be welcomed in one region while condemned in another.

Meta’s DNA has always leaned toward openness and spontaneity — values that Zuckerberg sees as essential. But this vision has repeatedly clashed with users’ expectations around privacy and control. His challenge in running a social network has been navigating the tension between a world where information flows freely and one where people feel secure in their digital lives.

The Other Side of Zuckerberg: Loyalty, Commitment, and Character

Few leaders have shaped a company with as much conviction as Zuckerberg. His unwavering focus, paternalistic leadership, and long-term mindset has shaped Meta’s trajectory and drawn intense debate. To some, he is a leader who always gets what he wants. But reducing Zuckerberg to a ruthless, power-hungry CEO ignores an important dimension of his character — his sense of loyalty and moral compass.

One of the most telling examples of this is his deep respect for Donald Graham, the former CEO of The Washington Post and Zuckerberg’s early mentor. When the time came to accept capital from Accel Partners — effectively moving on from Graham’s backing — Zuckerberg struggled immensely.

As detailed in The Facebook Effect by David Kirkpatrick, when presented with a much higher offer, Zuckerberg was overcome with guilt, feeling that taking the deal would be a betrayal of the commitment he had already made to Graham. The weight of this decision hit him so hard that he excused himself, only to be found sitting on the bathroom floor, crying. Through his tears, he was saying:

“This is wrong. I can’t do this. I gave my word!”

It was not the reaction of a cold, calculating businessman but of someone tormented by the idea of breaking his promise.

Struggling with the decision, he called Graham, and said:

"Don, I haven't talked to you since we agreed on terms, and since then, I’ve received a much higher offer from a venture capital firm. And I feel I have a moral dilemma."

Zuckerberg wanted the better deal but also felt bounded by his word. Graham, though disappointed, was not offended. Having already spoken to Accel’s Jim Breyer, he knew he couldn’t match the offer. What struck him most was Zuckerberg, at just 20 years old, wasn’t calling to break the news — he was calling to seek guidance. It was a level of thoughtfulness and maturity that left a lasting impression on Graham.

This moment offers a glimpse into Zuckerberg’s integrity, revealing that despite his controversial decisions, he is not purely driven by ambition or self-interest. Beneath his often-misunderstood persona, he cares deeply about honoring his word, even when it comes at great personal cost.

However, Zuckerberg is not infallible. While he has shown remarkable conviction in his decisions, he has also demonstrated the humility to acknowledge mistakes, apologize, and course-correct when necessary. Unlike many leaders who deflect blame, he has consistently owned up to the company’s failures — whether it was the missteps with Beacon, the fake news problem, or the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Rather than distancing himself, he has publicly apologized, testified before Congress, and implemented structural changes, such as launching the Oversight Board to improve content moderation. He has also emphasized that Meta isn’t perfect, acknowledging that companies like his should be held accountable for their mistakes. This willingness to face scrutiny and evolve shows that, despite his unwavering ambition, he learns from failures, adapts, and continues shaping Meta’s future with a long-term mindset.

Zuckerberg’s decisions have consistently shown that financial gain was never his primary motivation. He was never the type of founder looking for a quick exit or a massive payday. At just 22, he turned down a $1 billion acquisition offer from Yahoo! — an almost unthinkable move given Facebook’s position at the time. The company was generating roughly $30 million in revenue but was still unprofitable, and Zuckerberg himself would have walked away with $250 million. But he believed Facebook’s long-term potential was far greater. Many saw this as reckless, but to him, it was an obvious choice.

Zuckerberg has often stated in interviews over the years that if you were to ask his friends or those who know him well, they would say he’s never been particularly interested in money. Moreover, during a conversation with venture capitalist David Wolf, Zuckerberg was asked why he didn’t just sell Facebook and become very wealthy. Wolf had just visited Zuckerberg’s modest studio apartment, which was sparsely furnished — just a mattress on the floor, scattered books, a bamboo mat, and a single lamp. But Zuckerberg simply replied:

“You just saw my apartment. I don’t really need any money. And anyway, I don’t think I’m ever going to have an idea this good again.”

This moment underscored his mindset — he wasn’t driven by wealth but by the belief that Facebook was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reshape how people connect.

This isn’t to say he doesn’t care about power or influence, because he clearly does. But his ambition is rooted in control over the future of technology, not in personal materialism. For him, the company has always been about shaping the digital world, not just maximizing his bank account.

Zuckerberg’s Playbook: Acquire, Copy, Evolve

Zuckerberg has consistently demonstrated a keen ability to neutralize competitive threats, either by acquiring emerging rivals or by integrating their most successful features into Meta’s ecosystem. His approach is not merely reactive; it is a carefully crafted strategy that revolves around identifying successful trends, replicating and refining them, and ultimately leveraging Meta’s vast distribution power to scale them beyond the reach of competitors. This long-term focus, combined with a patient approach to monetization, sets him apart from many others who often prioritize short-term gains.

This approach has also sparked criticism, with some arguing that Zuckerberg’s strategy lacks true innovation, as it heavily relies on copying ideas rather than creating entirely new ones. Though this perception persists, his ability to refine and execute at scale has repeatedly proven to be a winning formula. While anyone can copy, execution is what truly sets companies apart.

The real differentiator for Meta is the ability to refine, optimize, and seamlessly integrate these ideas into a broader ecosystem, ensuring their long-term success. This process, which unfolds over several years, highlights Zuckerberg’s patience and strategic discipline, allowing Meta to stay ahead of the competitors. The following examples show Meta’s track record executing this strategy:

In 2009, Facebook responded to the rise of Twitter by incorporating status updates directly into its News Feed, diminishing Twitter’s differentiation as a real-time sharing platform;

In 2012, just before its IPO, Facebook made a bold pivot to mobile-first development, scrapping its HTML5 app and rebuilding native apps to improve the user experience. The same year, Zuckerberg recognized the growing importance of mobile photos and acquired Instagram for $1 billion — an amount seen as excessive, especially for a company with just 13 employees and no revenue;

In 2014, Facebook acquired WhatsApp for $19 billion, expanding its footprint beyond traditional social networking;

In 2016, Facebook responded to Snapchat’s rising popularity by introducing Stories, which quickly surpassed Snapchat’s own version;

In 2020, in response to TikTok’s dominance, Meta launched Reels, leveraging Instagram’s massive user base to compete in the short-video market; and

In 2024, Meta began experimenting with a fact-checking system resembling X’s Community Notes, underscoring its continued practice of learning from competitors.

But not all threats could be neutralized through acquisition or feature replication. One of the biggest disruptions Meta has faced in recent years came not from a social media competitor, but from Apple’s 2021 App Tracking Transparency (“ATT”) update. ATT fundamentally altered the digital advertising landscape by requiring apps to ask users for permission to track their activity across other apps and websites. This seemingly simple policy change had profound consequences for Meta’s business, as it significantly reduced the company’s ability to gather detailed user data for ad targeting.

The immediate impact of ATT was severe; Meta had long relied on third-party tracking and behavioral data to optimize its ad delivery. With ATT, much of this granular data vanished overnight. As a result, ad targeting became less precise, attribution models collapsed, and advertisers struggled to measure the effectiveness of their campaigns. Meta estimated a $10 billion loss in ad revenue in 2022 alone, largely due to the loss of tracking signals, which disrupted its ad targeting capabilities and reduced advertiser confidence.

Meta’s challenges were compounded by the fundamental difference between its ad model and Google’s. While Google captures high-intent users actively searching for products, Meta operates as a top-of-funnel discovery platform, relying on behavioral signals to match users with relevant ads. With ATT limiting those signals, Meta had to quickly rethink its approach.

Faced with this existential challenge, Meta adapted by pivoting towards AI-driven advertising solutions. Instead of relying on explicit tracking, Meta invested heavily in machine learning models that inferred user intent based on broader behavioral patterns. Initiatives like Advantage+ Shopping Campaigns leveraged AI to dynamically optimize ad delivery, improving performance even with fewer data inputs. At the same time, Meta developed probabilistic attribution models, such as its Conversions API, which allowed advertisers to send first-party data directly to Meta, reducing reliance on third-party tracking. The company also embraced on-device processing and privacy-enhancing technologies, ensuring personalized ad experiences while complying with evolving privacy regulations.

Despite the initial disruption, Meta successfully rebuilt its ad targeting engine, and by 2023, the company’s revenue growth reaccelerated. AI-driven targeting had become a competitive advantage — enabled by Meta’s heavy investment in infrastructure, including data centers designed to power its probabilistic modeling. Unlike smaller competitors that lack the budget or scale to make similar investments, Meta’s ability to deploy vast computational resources has allowed it to refine its ad targeting capabilities, positioning it as a dominant force in digital advertising.

Zuckerberg’s ability to navigate crises and adapt to changing landscapes underscores his strategic approach to leadership. His long-term thinking goes beyond social media and digital advertising, extending into AI as well. By open-sourcing Llama, Meta is positioning itself as an industry leader in AI infrastructure, ensuring widespread adoption of its models while simultaneously challenging the dominance of closed AI ecosystems. Unlike competitors that restrict access to proprietary models, Meta’s approach allows businesses, researchers, and startups to build on its AI advancements, accelerating innovation while embedding its technology across industries.

This decision is not just about AI ethics or accessibility — it’s a strategic move; Meta’s open-source approach strengthens its position without undercutting revenue. Selling access to AI models isn’t Meta’s business model, meaning that openly releasing Llama does not threaten its financial sustainability or its ability to invest in research — unlike closed providers that must carefully balance openness with revenue protection. This unique advantage enables Meta to scale adoption rapidly without the trade-offs its rivals face.

Moreover, Meta’s open-source approach increases AI adoption for companies. Instead of paying high fees for proprietary AI models or being locked into closed ecosystems, businesses can fine-tune and deploy Llama models on their own infrastructure or through cost-effective cloud solutions. This reduces reliance on expensive API-based AI services and gives enterprises greater control over customization, security, and long-term operational costs. By lowering the financial barriers to cutting-edge AI, Meta ensures that its models become deeply integrated into enterprise applications, research institutions, and emerging AI-powered tools.

Additionally, open-sourcing Llama doesn’t necessarily mean Meta is giving away a dominant advantage. AI is evolving at a breakneck pace, and the field is inherently competitive, with rapid iteration, breakthroughs, and increasing compute power shaping its trajectory. Even with open access, staying ahead in AI requires continuous innovation, top-tier research talent, and massive infrastructure — all areas where Meta already has significant strengths. Instead of trying to maintain an artificial lead through secrecy, Meta’s approach ensures that it remains a central player in the AI ecosystem while benefiting from widespread adoption and external contributions to its models.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where Llama becomes the standard, much like Linux did in cloud computing. Just as Meta has leveraged its massive distribution network to dominate social media, it is now leveraging open-source AI to expand its influence far beyond its core platforms, reinforcing Zuckerberg’s ability to think in multi-year horizons and setting Meta up for long-term technological relevance.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where Llama becomes the standard, much like Linux did in cloud computing. Just as Meta has leveraged its massive distribution network to dominate social media, it is now using open-source AI to expand its influence far beyond its core platforms. The rapid adoption of Meta AI, its chatbot integrated across Instagram and Facebook, exemplifies this — already reaching 700 million monthly active users and projected to hit 1 billion by 2025, largely due to Meta’s unparalleled reach. Beyond ecosystem expansion, staying at the cutting edge of AI also strengthens Meta’s ad model, improving its ranking and recommendation algorithms — key drivers of engagement and monetization. This reinforces Zuckerberg’s ability to think in multi-year horizons and positions Meta for long-term technological relevance.

As venture capitalist Alex Rampell, a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, once said:

“The battle between every startup and incumbent comes down to whether the startup gets distribution before the incumbent gets innovation.”

Zuckerberg has mastered both sides of this equation. By leveraging Meta’s vast distribution network, he has consistently out-innovated competitors — whether through acquisition, internal development, or strategic adaptation. In doing so, he has ensured that Meta remains a dominant force in the ever-evolving digital landscape.

Investing for the Future

Phil Fisher’s Scuttlebutt Method, outlined in Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits, evaluates whether management is proactively developing new products and innovations beyond their current growth cycle. Specifically, point 2 of his 15-point checklist asks:

“Does the management have a determination to continue to develop products or processes that will still further increase total sales potentials when the growth potentials of currently attractive product lines have largely been exploited?”

By this measure, Zuckerberg clearly fulfils it. Rather than resting on the success of Facebook’s core social media platforms, he has continuously reinvested into the future, betting on Augmented Reality (“AR”), Virtual Reality (“VR”) and the Metaverse as the next frontier of computing. His commitment to long-term innovation is evident in Meta’s multi-billion-dollar investments into Reality Labs, developing technologies that aim to reshape how people work, interact, and experience digital environments.

However, this aggressive push into AR/VR drew significant backlash from investors, who questioned the financial drain and the uncertain timeline for returns. But in true Zuckerberg fashion — the paternalism at play — he stood firm, insisting that these investments were necessary for Meta’s long-term success, positioning the company for the next evolution of computing beyond social media.

This strategic pivot is also deeply influenced by Meta’s experience with Apple, which controls the dominant hardware ecosystem (iOS and the App Store). After facing restrictions due to Apple’s privacy policies — most notably the ATT changes, which severely impacted Meta’s ad business — Zuckerberg recognized the risks of being dependent on platforms owned by competitors. By pushing aggressively into AR/VR and building its own hardware and software ecosystem, Meta aims to reduce its reliance on Apple and position itself as a leader in the next computing platform.

Zuckerberg isn’t just focused on optimizing current business lines; he is playing the long game, reinvesting profits to shape the future rather than simply maximizing short-term earnings. In my view, only founders with significant control over their companies can truly commit to long-term bets like this. Unlike professional CEOs who are often constrained by quarterly earnings pressures and shareholder expectations, founder-CEOs with significant voting control — like Zuckerberg — have the latitude to sacrifice short-term profits in pursuit of transformative innovation. Without this level of control, it’s tough for a company to willingly pour billions into a project like the Metaverse, where the payoff could take a decade or more.

Conclusion

At just 40 years old, Zuckerberg’s tenure at Meta is far from over, and his role in shaping the future remains pivotal. His leadership has been controversial, but his ability to navigate crises, outmaneuver competitors, and take bold bets on the future is undeniable.

At the core of Zuckerberg’s vision is his belief in the fundamental human need for connection. As he once stated:

“People have this deep thirst to understand what’s going on with people around them.”

This insight underscores the enduring strength of social networking — not just as a business model, but as a fundamental human need. While critics have accused him of being too idealistic or too aggressive, the reality is that he has consistently scaled products and platforms that cater to this intrinsic desire for connection, discovery, and shared experiences. Whether through AI, the Metaverse, or future technologies yet to emerge, one thing is clear — Zuckerberg is playing the long game.

Despite Meta’s massive network effects, Zuckerberg himself remains the company’s ultimate moat. His vision, execution, and control have shaped Meta’s trajectory, and as long as he remains at the helm, his influence will continue to define its future.

Disclaimer: Please note that none of the information provided constitutes financial, investment, or other professional advice. It is only intended for educational purposes. We have a vested interest in Meta Platforms. Holdings are subject to change at any time.